'Maria Cruz: One Million Dollars', Artspace, Sydney, 27 September to 21 October 2006, originally published in Artspace Projects 2006, Artspace, Sydney, 2007, pp. 101-8 (and swiped from Maria's website).

|

Maria Cruz, One million dollars

Installation view, Artspace, Sydney, 2006 |

In his

first major work, Giorgio Agamben sought to explore the peculiar duality in the thinking of art, the doubling that takes the form of a split between

poiesis, making, the production of sense, and

aesthesis, sensing, the apprehension of sense; that is to say, between art as the creative activity of the artist and art as it is experienced by the spectator. And while it was principally the more violent manifestations of this split that Agamben, invoking the principle according to which ‘it is only in the burning house that the fundamental architectural problem becomes visible for the first time’, dealt with as a means of glimpsing the original project of Western aesthetics, the suggestion remains from his analysis that the tension between poiesis and aesthesis is common to all artistic works; certainly to their presentation, their potential to be encountered. Maria Cruz’s

One Million Dollars project, undertaken at Artspace as a studio residency and gallery installation in 2006, represents a single instance that might be considered illustrative in this regard; exemplary, perhaps, because of the subtle way in which it dramatises what Agamben describes as both the ‘speculative centre’ and the ‘vital contradiction’ of art in our time.

To the casual viewer,

One Million Dollars consisted of three physical elements staged in a gallery setting. The dominant element was an entire wall layered from floor to ceiling with overlapping black and red dots applied in heavy acrylic, each around two centimetres in diameter, arranged in accordance with no visible system. In the centre of the space, brightly coloured party lights dangled from the roof beams; the bulbs themselves had been crafted haphazardly from some rough material and hand painted, but their fixings and the electrical cord that strung them together were authentic and, one would assume, operable. On the gallery’s front desk, which also occupied the space, sat a stack of photocopies of a paint-stained two-page spread from a graph-ruled notebook, handwritten entries listing nothing more than dates and a series of numbers: ‘Sept 9. 280, 920, 200, 134’; ‘Sept 10. 528, 528, 528, 945, 870’; and so on.

The immediate correlation between the three elements, other than their spatial convergence, was an aesthetic consistency. They shared the same pure hues, the same plasticity, they were each ‘painterly’ in the broad sense that they bore the trace of the artistic gesture — they were discernibly products of the same artist. There was little attempt at artifice, no apparent desire to appear polished or prefabricated, only the minimum requirement that they maintain their form for the duration of the exhibition, and that, like stick figures, they act as shorthand ciphers for what they were intended to be, or rather, to represent, where representation might be required. But at the same time the presentation was sparse, considered; it lacked the overloaded anti-aesthetic sensibility of the sort of process art that seeks to resist or otherwise deflect its inevitable manifestation as sense-producing data. The selection of elements appeared specific, as if anything superfluous has been edited out. Their configuration in the space may not have been particularly legible insofar as no meaning or intention was immediately conveyed, but there did appear to be a particular logic to their inclusion. Each had a reason to be there according to a certain teleology: it had a purpose. As much as it was indisputably an object,

One Million Dollars was also, quite clearly, a project.

Looking back over Cruz’s recent practice, we can see that this duality between project and object, between work as labour and work as product, is far from uncommon. The most significant — or, more properly, sustained — outcome of this tension, if we are to consider it as dialectically generative, has been the enormous quantity of

Yoko Ono paintings that Cruz has dedicated herself to producing since 1999. In this series, each title of Ono’s recorded output is rendered in two colours in simple sans-serif capitals on the unadorned ground of its own discrete, modestly scaled canvas. While these are reasonably strict parameters, the artist’s means of addressing them has varied playfully over time. In the first major presentation of these canvases, 2000’s salon-style

Feeling the space, Cruz confronted viewers with a rich wall of colour, the juxtaposition of contrasting hues producing quite striking optical effects. Just over a year later,

The hard times are over offered a more restricted pallet, reds and blacks on white whose economy privileged the evocative language of the song titles over their visuality, but whose constructivist genealogy implied that they be read within the broader context of art history.

These shifts suggest that the orientation toward process in Cruz’s practice is more pragmatic than programmatic. On the one hand, many artists have insisted that instituting a framework facilitates production insofar as aesthetic decisions only have to be made once. In the case of the Yoko Ono works, the subject matter, general form and individual titles are determined in advance, and while the quantity is not fixed — Ono has released more recordings since Cruz’s project began — it is still, to some extent, beyond the artist’s control. But on the other hand there is no direct elision of the aesthetic, of the work’s function as a sense-producing object. Like the rules of a game, Cruz’s parameters create a space for play, allowing the artist to engage with the sensuousness of the mark-making process without denying the viewer the opportunity to do the same. As Robert Ryman once put it in relation to his own evacuated canvases, such play-tactics within strategies of reduction allow for ‘clarification of nuances in painting’. In Ryman’s terms, the question is not what to paint, but how. And while this process is geared towards production, there is no attempt by the artist — by Cruz or indeed by Ryman — to channel that production away from its ultimate manifestation in the form of an object, an encounter, a thing.

|

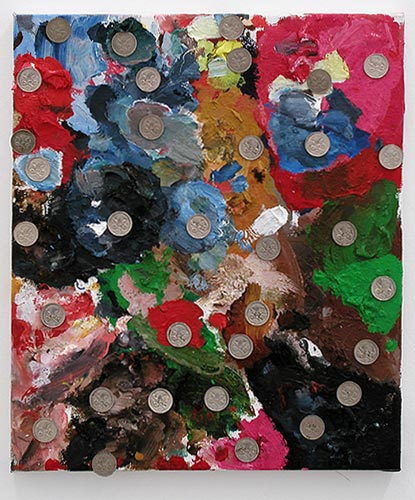

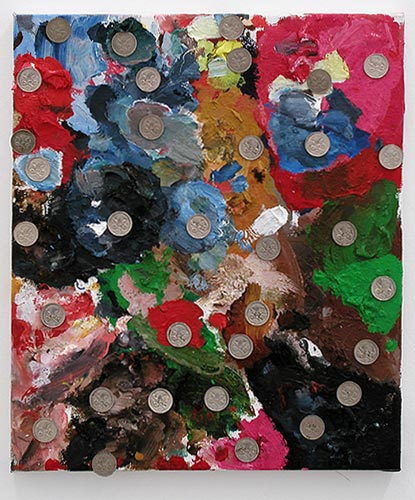

Maria Cruz, Palette (with coins) 2002

Oil on canvas, Australian 5 cent coins, 35.5 x 30.5 cm |

Correspondingly, Cruz maintains an awareness of the symbolising function of her work, even when working non-figuratively. This is best illustrated in the series of paintings that served, appropriately enough, as the means by which the productive framework for

One Million Dollars was developed, and it is here that we might begin to understand the logic behind this last work’s material realisation. Undertaken in close parallel to the Ono canvases, both chronologically and conceptually, these works in turn find their point of departure in three small paintings produced in close succession between 2002 and 2003. The first,

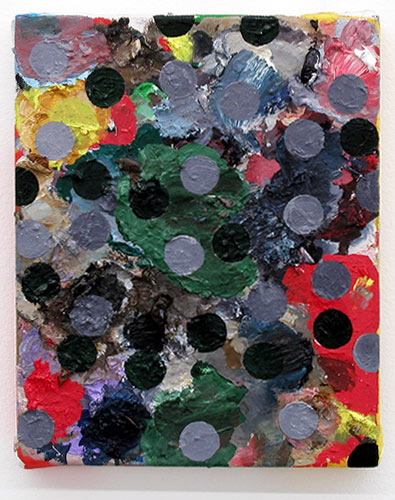

Palette #2, consists of a ground of heavily textured hues resembling an artist’s palette — one of the tools utilised in the work’s production — onto which are placed thirty-three Australian five-cent coins. The second,

Palette #7, duplicates the relationship between a daubed, polychromatic ground and an overlay of circular, coin-sized forms, but is executed entirely in paint. The appearance of the disks that make up the painting’s foreground is clearly derived from the coins in

Palette #2, to the point of their black, grey and virescent hues alluding to the unique grubby lustre of the five-cent pieces, but their surfaces reveal no face value, only traces of painterly gesture with no obvious reference to their formal origin. A third, untitled, painting from 2003 discards the palette ground entirely, the artist having opted instead for a flat base onto which the disks are applied thickly but evenly in such a way that each forms a discrete, monochromatic plane. While the restricted colour range of the preceding work is retained, the green in the third work is more pronounced, and it is presented in several different but clearly defined shades that substitute the grubbiness of the coins for the luminosity of pure hue.

|

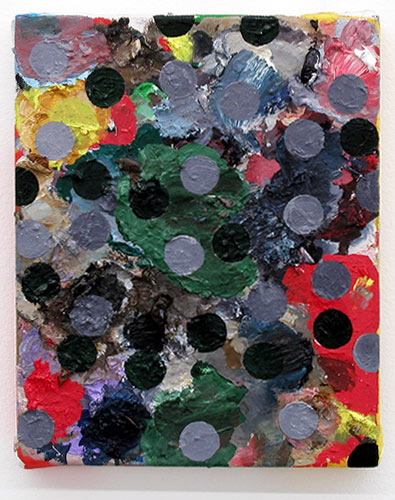

Maria Cruz, Palette (traces of coins in grey) 2002

Oil on canvas, 25 x 20.5 cm |

Over the course of the three paintings, we see a shift from the use of painting as a mimetic technology, as a process that would represent or refer in some way to the coins, toward a foregrounding of the abstract sensuality of the paint itself. This aspect is emphasised by the edges of the disks actually overlapping in the final work with no dilution or mixing of shades, an effect that could only be achieved by allowing each successive layer of paint to dry completely before another is applied. Through the use of this method, the artist introduces to the work a depth of field, but also — and inseparably for the viewer — a temporal aspect, a simultaneous privileging of the visual and a sense of time spent in the production visual, which when combined characterise the artist’s activity not as painting something, but as painting as such.

What makes the differences between the three works more pronounced, however, is that Cruz’s practice does not deal exclusively with abstraction; indeed, a good deal of her work is testament to her skill as a figurative painter. This is not a general shift away from representation, but a particular one, and could only have been prompted by a realisation arrived at in the course of presenting the first work. And that is that money, while an object like any other — or, to be precise, a quantity of metal with a fixed weight — has, at least in the context of liberal-capitalist society, a signifying function that is not only

excessive, as with all signification, but

irreducible — an excess that no recontextualisation can alter — and that, for an artist interested in dealing exclusively with its formal qualities as an object, systematic abstraction is the only option short of total revolution.

What is this irreducible signifying function? We know from Marx that the substance of value is labour, that the value of a given commodity, when brought to exchange, is determined not by its usefulness but by the amount of abstract labour-time, the average unit of total sensuous human activity, expended in its production and distribution. This, perhaps the most contested of Marx’s theories — insofar as critiques of Marxism are actually directed at the work of Marx himself — should not be construed as a simple economic proposition but as a social one. As an exchange value, the commodity is at once the physical embodiment of a certain social relation between producers — between, putting it very crudely, property owners and propertyless workers — and the concealment of that relationship. It is the appropriation of the productive capacity of humans made rational, ‘the definite social relation between men themselves’ assuming ‘the fantastic form of a relation between things’. Money’s irreducible excess of signification lies, therefore, in its role as universal equivalent, as the commodity form

par excellence, standing in for all other commodities as the social incarnation of human labour and the ultimate manifestation of the activity of alienation that labour constitutes (which of course for Marx represents the appropriation of humanity’s very essence).

If Cruz’s strategy of introducing practical parameters to reduce the number of necessary aesthetic decisions is understood as a decentring of ‘the primacy of individual subjectivity as the locus of art production’, as it was for the early conceptual painters, then it is appropriate that the artist should also problematise the metaphorical aspect of the art object. Rather than originating in a rhetorical denial that such a function is possible, however, the process of abstraction as seen over the course of the three coin paintings instead demonstrates a tacit acknowledgment of money’s irreducible excess of signification, an awareness that dealings in the metaphorical, especially in such loaded territory, have the capacity to be wildly misread, forcing the responsibility for aesthetic judgment back on the artist and postponing further artistic production until such judgments can be made.

Of the three coin paintings, it was the third that would serve as the template for the body of work that would develop out of this process, representing the point at which the artist found her parameters comfortable enough to institute a new system of making. While the shape and size of the small circles that are central motif of these subsequent works hark back to the coins from which their forms were derived, reference to the social and cultural significance of this originary material is kept in abeyance, with the artist effectively excluding it from the visual field. Furthermore, the works’ titles —

One Thousand Nine Hundred Seventeen;

Eight Hundred Forty Five;

Three Thousand Twelve — are little more than reflexive allusions to the process of the paintings’ construction, announcing nothing more than the total number of ‘dots’, visible and hidden behind others, contained within their individual pictorial planes.

|

Maria Cruz, Three hundred forty eight 2005

Oil on primed lined, 40.7 x 31 cm |

Exclusion, though, is never absolute. Whatever is excluded must bear a relationship to that which it is excluded from (or which excludes it), and in the necessary reciprocity of this relationship there is a paradoxical inclusion in the form of immanent potentiality. A thing is included insofar as it is not. Thus, the elision of the signifying power of money haunts the body of work that proceeds from the first coin painting as an unresolvable tension, regardless of the individual characteristics of the objects themselves: they are products of a project from which it has been consciously excluded. Importantly, though, this is a tension that can only be felt by the artist as definer and executor of the project, and only understood by the informed viewer as witness to that definition and execution; the objects themselves do not betray it. And so to the two tensions already underlying Cruz’s practice — project and object, inclusion and exclusion — is added a third, that between making and sensing, between poiesis and aesthesis.

It is possible that these hitherto subliminal tensions within Cruz’s practice emerged because of the gravity of the project.

One Million Dollars marked both the culmination of the process developed in the coin paintings and a substantial shift in its articulation. While the earlier paintings had sat discretely within the frame of small canvases, all of which were well under a metre square, the painted component of

One Million Dollars occupied an entire wall almost six metres long and over three metres high. Moreover, the work could in no way be considered as painted component alone, accompanied as it was by a sculptural element, the string of roughly crafted party lights, and a documentary element in the form of the stack of photocopied workbook pages, and therefore could no longer be considered as simply pictorial, but as spatial, temporal and discursive.

|

Maria Cruz, One million dollars

Installation view, Artspace, Sydney, 2006 |

If we are to follow the logic behind the quantitative titling of the coin paintings, the sampling of diaristic entries in the workbook could be read as a register of the number of dots painted in each session, emphasising the sense of temporality already present in the layering of different colours. As the record of an activity, the photocopies performed a second, related operation as a kind of Brechtian

Verfremdungseffekt, albeit an obliquely poised one, geared toward demystifying the physical processes behind the work’s fabrication — an afterthought, perhaps, but a significant one. Most pointed, however, was the return the excluded signifier, money, physically in the poverty of form of the party lights — self-consciously cheap approximations of a cheap emotional effect — and discursively as outright acknowledgment in the project’s title. Each small red or black disk being roughly the size of an Australian one-dollar coin, the work was, tautologically, one million dollars. Or at least it aspired to be one million dollars; the amount has too much cultural resonance, acting still, in spite of inflation, as the figurative horizon of wealth to the non-wealthy, to have been arrived at after the fact by Cruz, as a precise representation of the quantity of dollar-sized circles making up the wall painting. In any case, the sheer scale of the work, the overlapping layers of paint and the limitations of the selection from the artist’s workbook — it is clear from the page that it only covers a short period of the time invested in the work — mean that there is no way for the uninformed viewer to know whether exactly one million dots were actually painted, or even how close the artist came to that figure.

Here again we find the work’s dramatisation of the split between art as experienced by the artist and art as experienced by the viewer. By presenting the diary excerpt, whose suggestion that the object is also a project ironically also presents the project as an object, and by confronting the question of value through the work’s sculptural element and its title — which is itself both proscriptive and elusive — Cruz placed her creative activity as an artist on the same plane of visibility as the product of her labour, but did not, could not, provide access to the authentic experience of that activity. Instead,

One Million Dollars operated as a zone of indistinction between poiesis and aesthesis, between the provision of sense and its apprehension, painting as performance performing as painting. And located within this zone, hovering there still, were those questions, ever-present even in their absence, of value and work — work as labour, as product, as creative activity, work as the operation of the work, as the creation of human essence and its appropriation and alienation — frustratingly, yet tantalisingly, unanswered.